Let the Meitei learn to be happy within their ancestral land. Sana Leibak is a 650 sq. mile kingdom, and they are very, very proud of their rich cultural heritage with their 4th BC founding civilisation. The problem starts when they try to put their hands on our land. They are the majority, but that doesn’t mean that they have the legitimate right to govern the tribal land as they wish. It is scrutinised and protected by the Constitution of India (371C). They try to act oversmart by trying to assert themselves as tribal, which is such a sinister design against the hill tribes, especially the Zo ethnic groups.

They chose to become a General Category at the same time they were privileged to enjoy the VIIIth Schedule, wherein the Indian Constitution enlists Manipuri as one of the 22 official languages of India. They are as follows: Assamese, Bengali, Gujarati, Hindi, Kannada, Kashmiri, Konkani, Maithili, Malayalam, Manipuri, Marathi, Nepali, Odia, Punjabi, Sanskrit, Santhali, Sindhi, Tamil, Telugu, Urdu, Bodo, and Dogri.

So, today, I have a plea to them: let them totally put their hands away from the lands of the hill tribes. The hill tribes joining the state of Manipur itself is their gain. That is all that the hill people can offer to them, but not their land and administration. They are trying to handle too many illegitimate things which are going against the constitution. Out of the 60 seats in the Manipur Legislative Assembly, 40 are in the Valley and 20 are in the Hills. This ensures that the Meitei community effectively controls the state government and budgetary allocations.

The Hill Areas Committees (HAC), designed to give tribes autonomy over their own affairs, often clash with the state government over issues of forest land surveys and “protected area” designations, which tribes see as a pretext for land encroachment. Article 371C provides for a special committee of the Legislative Assembly consisting of members from the Hill Areas. Tribes argue that the state government frequently undermines this committee’s authority to push through policies affecting the hills. For the Zo ethnic groups, the preservation of land is not just economic; it is central to their identity.

The movement for “Separate Administration” has grown out of the belief that a Meitei-led government cannot impartially govern our tribal lands, and this is our right; if that right is taken away, we are culturally, physically and emotionally gonna be extinct, as if it is wiped away by tides and waves.

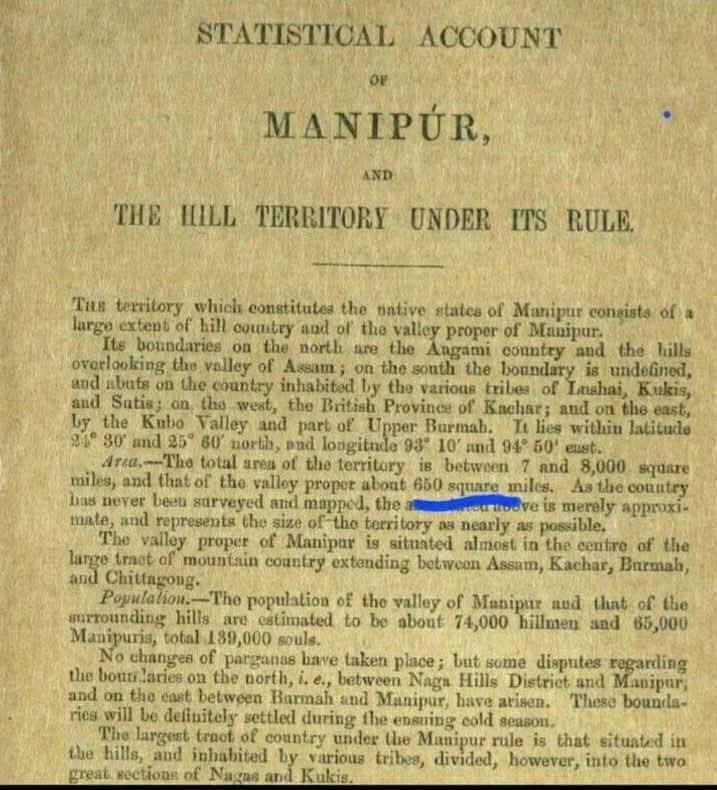

The Merger Agreement, signed on September 21, 1949, between the Maharaja of Manipur and the Government of India, led to Manipur becoming a Part C State and later a Union Territory and full state. Here the Meitei themselves think that agreement preserved the territorial integrity of the ancient kingdom, often referred to as “Sana Leibak,” and they falsely believe that their merging with the Union of India encompasses both the valley and the surrounding hills. The surrounding hills, esp. the Zo areas, are never included in the agreement of the Accession. The original document clearly stated that the area of the merger with the Union of India is just 650 sq miles, and this is evident today for the hill tribes, esp. for modern-day Southern Manipur.

We, the hill tribes, particularly the Zo groups, argue that our ancestral lands were never formally part of the Maharaja’s administrative domain in a way that granted the state government absolute authority over us. We maintain that the hills were always autonomous regions governed by our own customary laws before we joined present-day Manipur. Now, we were called and termed with nasty narratives, like ‘outsiders’ and ‘refugees’. We have no place in the core of Manipur, so the only way possible to move forward is to let the Meitei get back their original territory.

It is hard to understand why the Meiteis vividly think that the land of the hill tribes belongs to them! This is a bit of a shameful act, even to think that way for the Meiteis. Article 371C is meant for the hills in the form of the Hill Area Committee and the Manipur Land Revenue and Land Reforms (MLR&LR) Act, 1960), for the Meiteis. There is no same law for the Hills and the Valleys, looking back even to colonial times.

Even the mandates of the HAC (Hill Areas Committee) have been taken away, while the rest of all the NE states were being given VI Schedule provisions, but when it comes to Manipur, the Meiteis dictate theirs by saying “…with local adjustments”. All these are a sinister design where we as hill tribes were being marginalised but also ill-treated in the face of the sun. The main purpose of Article 371C is to ensure that the “majority” (the Meitei-dominated state government) cannot unilaterally impose its will on tribal lands. This exactly is the reason why I keep on saying that the Meitei cannot and should not control over our land, as it is enshrined in the constitutions.

If there is no such law, as mentioned earlier, the dominant community, or the greedy and ferocious Loktak river, will phinish the minority groups and the weaker section of the community. We as tribal groups argue that recent attempts by the state to conduct forest surveys or declare “protected areas, protected forests or reserved forests, wetlands, sanctuaries, etc.” were also published by the Meitei or the state government in the Gazette of India, which, by the way, is something unlawful, as they failed to take our consent as to which geographic zone and area should become farmland/wetland, animal sanctuaries, etc. Thus, all this is an evil, or better to say a devilish, play against the hill people. and it is really a “sinister design” that bypasses these constitutional requirements. There are several zones in India where land ownership by non-locals is either strictly limited or completely prohibited. These laws are generally in place to protect the cultural identity of indigenous communities, safeguard fragile ecosystems, or prevent the displacement of local farmers.