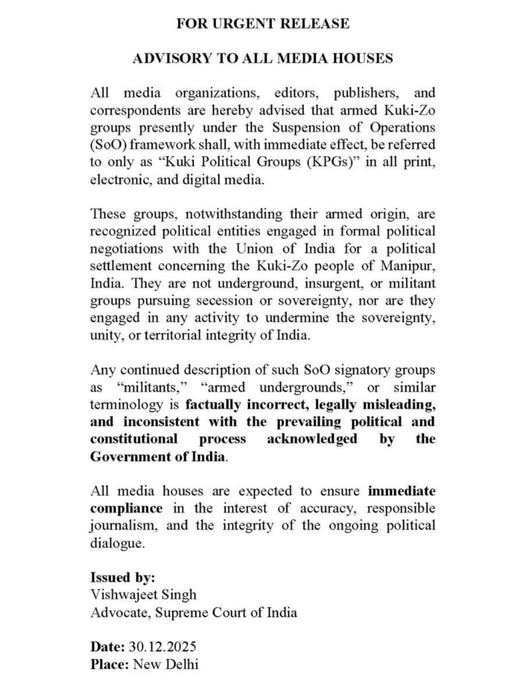

The attempt to legally mandate the term “Kuki Political Groups” is a blatant overreach that ignores the historical reality that identity can neither be asserted nor inserted by decree. For those of us who read colonial history, it is clear that “Kuki” is often a label of convenience used by outsiders, yet this advisory seeks to cement it as a political fact. I cannot find my end or my beginning with this name; it is a term that many tribes, particularly those identifying as Zo, have never collectively accepted. To be told how to identify by a legal representative is an insult to our ancestry, especially when only a select few agreed to this terminology while others were silenced or ignored. I will protest this mandate because it is factually incorrect and historically blind to the nuances of our lineage.

If we are Zo people, we cannot be forced to become “politically or colonially Kuki” just to satisfy a legal framework or a negotiation table. No court and no law can prevail when it attempts to overwrite the lived reality of a people. This is not about “accuracy”, as the advisory claims; it is about the forced homogenisation of a diverse group of people for the sake of administrative ease. We refuse to let our heritage be simplified into a single, disputed word. Furthermore, this advisory is legally misleading because it attempts to use the threat of “compliance” to stifle dissent and enforce a narrative that does not belong to us. The integrity of any political dialogue is compromised the moment it demands the surrender of one’s true identity. We reject this colonial-style imposition that treats our names as things to be traded or assigned. Identity is a sacred right of self-determination, and we will not stand by while a legal decree tries to “insert” a label that contradicts our history and our hearts. Identity is not a policy; it is who we are. In order to strengthen this argument and protest, I will be referring to specific historical records that validate the Zo identity over the colonial Kuki label. The British colonial administration prioritised categorisation for tax collection and border control, often ignoring the self-identification of the people they governed.

The Colonial Imposition vs Indigenous Reality: The term “Kuki” first appeared in British records around 1777, during the era of Warren Hastings, primarily as a vague label for “mountaineers” or “wild tribes” inhabiting the Chittagong Hill Tracts and the Lushai Hills. As it has been rightly noted, this was an external “assertion” by the British. In contrast, the internal “Zo” identity has much deeper, with indigenous roots even embraced by the intellectual Kuki themselves. The earliest European mention of the name appears in the accounts ofFather Vincenzo Sangermano, an Italian missionary who lived in Ava (Burma) between 1783 and 1806. In his work, A Description of the Burmese Empire (published in 1833), he recorded the people of the Chindwin area as “Jo” (a phonetic spelling of Zo), describing them as a distinct nation with their own customs and language. Further, the earliest recorded use appears in the works of Fan-Cho, a diplomat of the Tang Dynasty. He mentioned a kingdom in the Chindwin Valley whose princes and chiefs were called Shou (Zo)

This predates the widespread administrative use of “Kuki” and serves as a primary historical pillar for my dissenting to be called myself as Kuki. It is quite misleading why the mostly the Thadou speakers bluntly and blatantly accept Kuki as their true self and identity, which came out from nothing but from the coloniser. We are saying so because there was a name that had been used to address us in all aspects, which is valid historically and culturally, while the political terminology is not applicable in this case. Anyways, can we change identity or

The Linguistic Evidence: The most “authentic” colonial-era validation of your identity comes from Sir George Abraham Grierson in the Linguistic Survey of India (Vol. III, Part III, a series published between 1904 and 1909). Grierson was a meticulous scholar who realised that the British administrative labels were often flawed. He observed that while the government used “Kuki-Chin” as a linguistic classification, the people themselves did not use these terms. He noted that the tribes referred to themselves by indigenous names like Zo, Zou, or Yo. This linguistic record is a powerful tool to protest because it proves that even during the height of the British Empire, scholars recognised that the “Kuki” label was an artificial “insertion” that did not reflect the soul or the speech of the people.

The Failure of Legal Mandatory: When you’re looking at the colonial labelling, “Kuki” was born of colonial convenience; it cannot be “enforced” as a singular political identity today without erasing centuries of specific lineage. The advisory issued by the Supreme Court advocate attempts to restart a colonial process: defining a people from the outside in. However, history shows that identities like “Zo” are resilient because they are based on shared blood, language, and the “Jo” records of the Chindwin, rather than the bureaucratic needs of a central government. To force the “KPG” label onto a Zo-identifying person is not just a legal error; it is a violation of the historical record that has existed since before the British even arrived in the region.

Historical Argument:

The Lack of Evidence for “Kuki-fication”: There is no historical, linguistic, or ancestral evidence that justifies the forced assimilation of the Zo people into the “Kuki” label. As the timeline above demonstrates, the earliest and most authentic records—such as those by Father Vincenzo Sangermano—document the existence of the “Jo” (Zo) people as a distinct entity long before the British administrative machinery began its work. This missionary record is crucial because it captured the people’s identity before it was filtered through the lens of colonial frontier policy. It proves that “Zo” is not a subgroup of Kuki but Zo is a primary identity that stands on its own. Furthermore, the Linguistic Survey of India serves as a permanent scholarly rebuke to this modern legal advisory.

Sir George Abraham Grierson was explicit in his findings: the term “Kuki” was a word used by outsiders, not by the people themselves. By recording the names Zo, Zou, and Yo, the survey provided authentic evidence that the indigenous people maintained their own nomenclature in defiance of British labels. To ignore this scientific record in favour of a “political settlement” is to commit an act of historical erasure. There is simply no evidence in the roots of our language or the stories of our ancestors that makes us “Kuki”. Ultimately, identity is a matter of self-determination, not a legal mandate. This advisory is factually incorrect because it treats a disputed, colonial-era category as an absolute truth. If the historical record shows that we have identified as Zo since at least the 18th century, a legal decree in 2025 cannot “insert” a different identity. No court can prevail over the documented history of a people who refuse to be colonially defined. We will continue to protest this imposition, standing on the firm evidence of our past to protect the integrity of our future as Zo people.

The “Zo” Consciousness and the Limits of “Kuki”:

For those who identify as Zo (or Zomi), the term “Kuki” feels like a foreign garment that doesn’t fit. The “Zo” identity is rooted in indigenous nomenclature—found in folk songs, genealogies, and oral traditions that predate the arrival of the British. When a legal mandate insists on “Kuki”, it creates a genealogical erasure. If a community’s “beginning and end” are rooted in the concept of Zo-suan (descendants of Zo), being forced into a “Kuki” political bracket feels like being written out of one’s own history. It suggests that the state has the power to decide which part of an ancestor’s legacy is “politically relevant” and which is not.

The core of your protest lies in the rejection of a “label of convenience.” In the 19th century, the British Raj operated through a “Cartographic Mind”—a need to map, categorize, and bound everything they encountered. When colonial officers like Alexander Mackenzie or John Shakespeare encountered the diverse clans of the Indo-Burma frontier, they lacked the linguistic nuance to differentiate between the various Suan (lineages). The term “Kuki” did not emerge from the people themselves; it was an exonym derived from Bengali neighbors to describe “hill people” or “highlanders.” By adopting this term, the British created a “legal fiction.” They took a fluid, migratory, and clan-based society and froze it into a static administrative block. To mandate this term today is to validate a 150-year-old clerical error. It treats the administrative shorthand of a dead empire as a sacred political truth.

The tension between “Kuki” and “Zo” (or Zomi/Chin) is not merely a linguistic preference; it is a clash of worldviews. While “Kuki” is a term of external reference, “Zo” is an indigenous concept rooted in the very soil and soul of the people. The Sacredness of the Name: In the oral traditions of the Lushai, Paite, Vaiphei, Zou, and others, the term “Zo” appears in folk songs (Lano), chants, and genealogies that stretch back centuries before the first British surveyor arrived. The Problem of “Insertion”: When a legal representative “inserts” this identity into a mandate, they are attempting a cultural transplant. They are asking a people to replace their organic, ancestral identity with a “political brand” that was designed for the convenience of the state.

A “Beginning without an End”: As we all know, one cannot find their beginning in “Kuki” because “Kuki” has no root in the ancestral tongue. It is a plastic labellling, it would have been a result of a narrow consensus in the corridors of power, “representation” often becomes a tool for exclusion. It ignores the “silenced” voices—the elders who refuse to sign documents under a name they don’t recognize, and the intellectuals who see the long-term danger of ethnic homogenization. To mandate this name is to commit epistemic violence, forcibly aligning the “marginalized” with a category they never chose.

Violation of International Norms: From a legal philosophy standpoint, identity is a “non-justiciable” reality. The law can regulate behavior, property, and taxes, but it cannot regulate the internal sense of belonging. The United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP), specifically Article 33, states that “Indigenous peoples have the right to determine their own identity or membership in accordance with their customs and traditions.”

- It ignores the fact that identity is a “lived experience,” not a “legal status” to be conferred by a government official.

- A legal mandate that forces the term “Kuki” violates this principle.

- It bypasses “customs and traditions” and replaces them with “legislative fiat.”

Historically, the tribes of the region moved between identities based on alliance, geography, and kinship. By mandating a single term, the state is trying to stop a river from flowing. It ignores the nuances of lineage—the specific histories of the Simte, the Gangte, the Thadou, and others who may have varying degrees of comfort with the “Kuki” umbrella. To ignore these nuances is not just “factually incorrect”—it is a recipe for future conflict, as suppressed identities eventually reassert themselves against the “mandated” monolith.

Comparative Timeline, Zo vs. Kuki Identity Records:

a). Late 1700s (Fr. Vincenzo Sangermano): Recorded the people of the Chindwin area as “Jo” (Zo). This is the earliest primary evidence from an independent observer, predating British administrative labels.

b). 1777 (British Bengal Records): The term “Kuki” appears as a vague colonial category for hill tribes, used for external administrative purposes rather than internal identity.

c). 1904 (Linguistic Survey of India): G.A. Grierson authentically recorded that the people used their own names like Zo, Zou, and Yo, noting that “Kuki” was an artificial “insertion” by outsiders.

d). 2025 (Legal Advisory): The attempt to mandate “Kuki Political Groups” as a legal fact, which ignores the centuries of documented indigenous history and the right to self-identification.